2000+ years of sex workers and art 🏺

From hetairai on Ancient Greek drinking cups to Sinéad O'Dwyer's latest fashion show ❤️🔥

I’ve been chewing on this topic for about a week or so—ever since the internet started spiralling in response to Sinéad O’Dwyer’s show at London Fashion Week. There have been some great write ups of the show which I’ll whack at the end but I would strongly encourage you to check out the fashion designer herself, who consistently prioritises diversity and representation in a truly admirable way but also just makes really reeeally hot clothes which I am desperate to own one day. Check out her Instagram and website as the first step down this steamy rabbit hole 🐰

The main thing that sent the internet into a tizzy is the fact that O’Dwyer’s show included 3 pairs of scantily clad performers who clocked in and passionately made out with each other for about three hours 💋 The funnest of fun facts is that ALL the performers were queer women and 5/6 of them were current or former sex workers (this may also have contributed to said tizzy). It was visually gorgeous, the clothes looked fabulous, and it was just deliciously erotic. See for yourself.

Parts of the show were motivated by the designer’s goal to bring a runway experience to blind and low vision guests; O’Dwyer wrote that she “wanted to capture the tactility of the world through words.” A huge part of what made the show so sensational and impactful, however, is the way that she and her team flipped the traditional dehumanising objectification of sex workers, instead putting them front and centre, paying them (obviously), and actually celebrating their skills and talent. To quote Brit Lawson, writing for COSMO,

“It wasn’t commodifying sex work — it wasn’t even about sex work — but it put sex workers front and centre, purely for the skills they’ve gained in their chosen career.”

There’s also a wee bit of a personal connection here for me. The first time I came across Sinéad O’Dwyer’s work was with Charlie Ann Max, a [now] dear friend of mine who I first met two years ago. She invited me to a fashion show which in and of itself felt very chic/wildly above my pay grade as an ancient history nerd who’d just moved to London. O’Dwyer’s work, displayed on a wide range of bodies, was full of cut-outs, colour and fascinating silhouettes.

Seeing her collection coincided with a huge upswing in my own career. Meeting Charlie was a real turning point; I started co-hosting textile-free dinners with her and we ended up working together in London, Berlin and LA, so it all felt and continues to feel very serendipitous, as if the universe has conspired in quite a lovely way.

That’s as much of a love letter to Charlie as I’m allowing myself right now so let’s get back to the topic at hand. The angle I want to flesh out is, unsurprisingly, the historical one. And I’m not talking decades or even centuries when it comes to the objectification of sex workers in art, I am talking THOUSANDS of years. To be perfectly clear I am not a sex worker and therefore I am by no means qualified to speak on or write about their lived experience in the past or present (to that point, if you are and have thoughts/want to discuss this please comment or message me) but what I DO know is old, dusty, vaguely pornographic pots and thanks to the Ancient Greeks we have PILES of material to work with. Also I think it is important to contextualise boundary-pushing work such as O’Dwyer’s latest show within as broad a historical context as possible in order to better understand where certain responses (the aforementioned online tizzy) may be coming from and why exactly a show like this is so powerful.

In order to contextualise this fashion show within a few thousand years of history, I’m going to pull out two specific examples of sex workers in art (yes they’re both from ancient Greece and yes I’m sure there are 700 other examples I could’ve included but alas I am beholden to 1) my area of expertise 2) Substack’s email length limit). The prime example that springs out to me is Greek vase-painting from the Classical period (around 2500 years ago). To wrap up we’re going to cover the story of Phryne, possibly the MOST famous sex worker from the ancient world (she’s a real fan favourite and author Daisy Dunn recently spoke about her at a talk I attended so it feels rude not to).

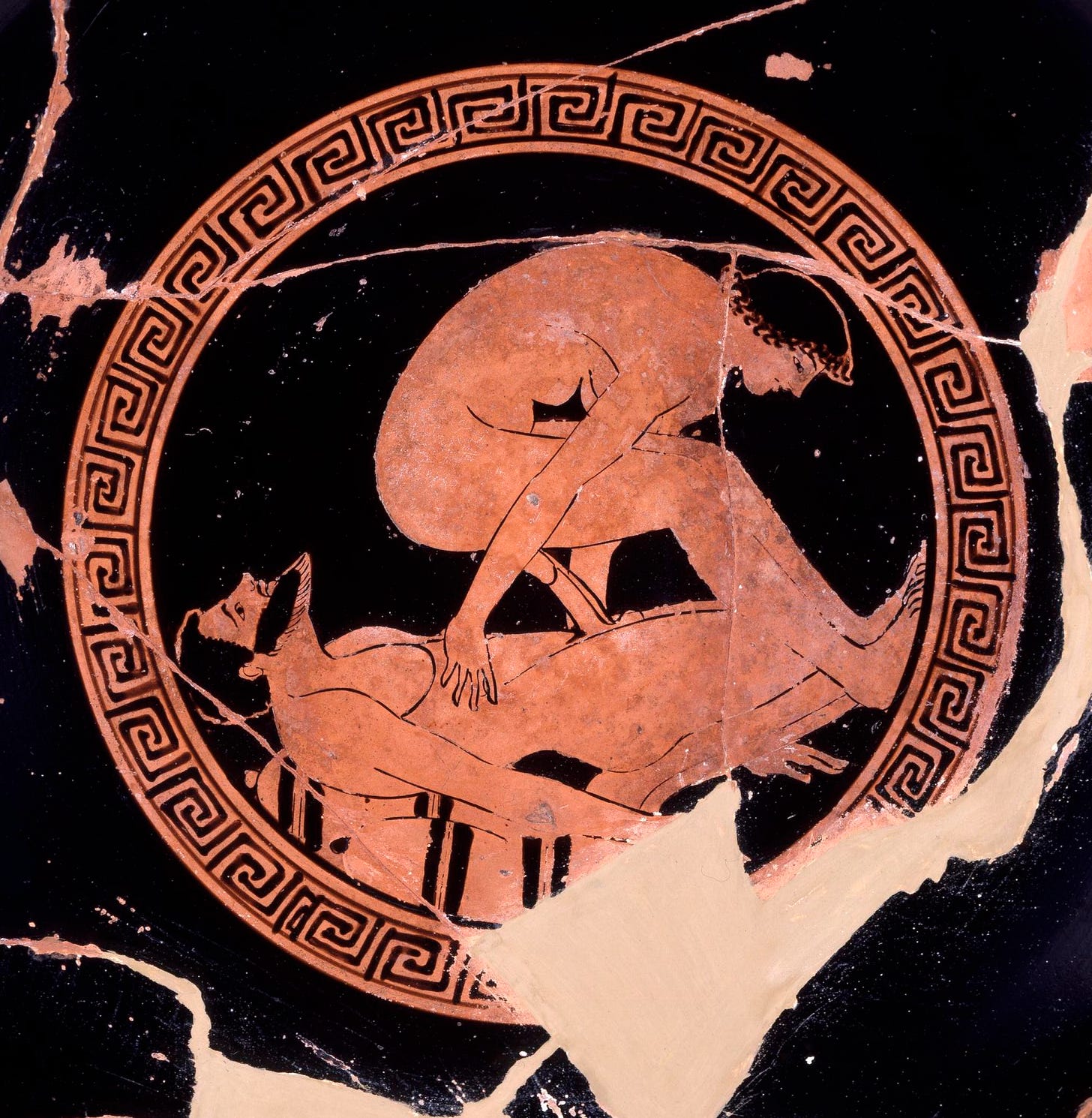

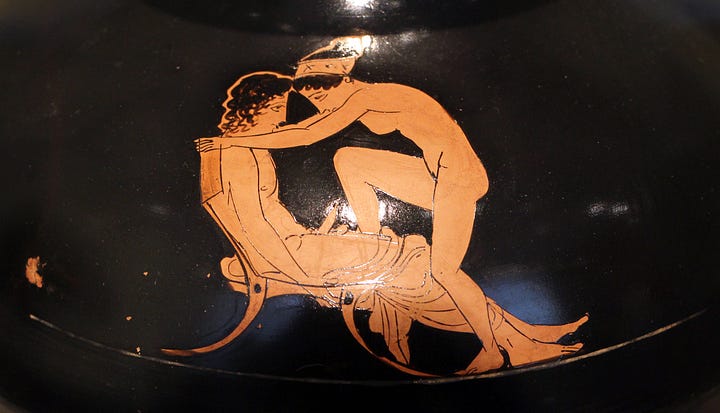

Now let me hit you with some background so you know what’s what. The ancient Greeks split sex workers into two main categories; pornê and hetairai. Pornê (or pornai, still a smidge unclear about plural and singular transliteration from the Greek) were ancient prostitutes, typically enslaved women who were owned by pimps, while hetairai were closer to what we would think of as high-class call-girls or courtesans. It’s difficult to fully map either of these categories onto our modern understanding of sex workers, especially as the written evidence we have is wildly biased and therefore wildly unhelpful, but the hetairai were a major subject of vase painting (and therefore this newsletter). The vase-painting you’ve already scrolled past shows two hetairai reclining at a symposium. Identifying them as ancient sex workers is relatively straightforward as we know that wives were contained to the household, they did NOT cop an invite to the symposium and they absolutely did NOT get their fun-bags out. Hetairai, however, were welcome at the symposium, yes for sexual/saucy purposes, but also because they were educated, skilled in arts and music (as well as sexual/saucy activities). They were seen to add to the intellectual pursuits of a symposia, as well as the erotic side of things.

Here is another example that showcases how the Greeks communicated a female figure’s status as a sex worker, nudity being a key part along with the directness of her gaze (I know demure is dead but still, not very demure). The two examples above employ both of these visual tropes but they also take it a step further; the hetairai are playing kottabos, a sympotic drinking game that was absolutely under no circumstances supposed to be played by respectable women. So yes they have their funbags out and that IS important, as is the fact that they are even being shown in a sympotic context, but the fact that they’re playing kottabos—a drinking game that is all about gaining erotic favour—is arguably more significant in that it’s more transgressive. Not to shoehorn an anachronistic or straight up ludicrous parallel or anything (watch me), BUT the idea of a transgressive elevation of status through art—the hetairai are depicted as active participants in the symposium—kind of/somewhat/absolutely evokes O’Dwyer’s show where she has elevated the status of sex workers, putting them front and centre and truly celebrating them.

Now MORE SMUTTY POTS.

This hetaira presents us with a slightly less aspirational scenario ~ she’s holding up the head of a symposiast who is vomiting on both of their feet?? Whatever she was getting paid, I’d wager it wasn’t enough.

This gal maybe (and I mean MAYBE) approaches O’Dwyer’s ethos; this hetaira is pictured showcasing her musical talent as she plays the aulos, the double flute. There is, however, a close association between aulos-playing and sexual acts, which we can see in this lovely quote from the one and only Aristophanes, a comedic playwright who was writing in the middle 5th and early 4th century BCE.

ὁρᾷς ἐγώ σ᾽ ὡς δεξιῶς ὑφειλόμην

μέλλουσαν ἤδη λεσβιᾶν τοὺς ξυμπότας:

[You see how deftly I sneaked you away, before you had to give blow-jobs to the diners.] Ar. Wasps. 1345-6.

He really had a way with words.

Here I’m really admiring her upper body strength more than anything. While I’m tempted to start ranting about her rather bored facial expression, the bloke doesn’t seem to be having a great time either (the Greeks weren’t exactly known for their talents when it came to painting facial expressions).

I LOVE this fragment and I LOVE her side eye. She looks completely ambivalent (and is also kind of breaking the fourth wall which is both disturbing and thrilling).

I mean giddy up 🤠 but this one does look a smidge more romantic and intimate, with their foreheads touching and their eyes locked on each other’s.

There are about a million more (some are somehow even more graphic) which I may end up posting in Notes but let’s wrap with this particularly cartoon-y askos, a little vessel that was used for pouring oil and other liquids.

All this to say, employing the image of a sex worker is by no means new—the ancient Greeks found it titillating and visually compelling enough to COVER their vases with paintings of them engaged in various aspects of their job, whether musical or straight up pornographic, so perhaps we could all benefit from getting a grip and un-clutching our pearls.

As I promised we are going to finish with Phryne, a fabulous/famous/infamous hetaira who was the girlfriend of the celebrated sculptor Praxiteles. She was so gorgeous she was said to be the model of his most famous sculpture, the Aphrodite of Knidos.

Natalie Haynes, writing about Phryne, points to her as evidence that hetairai had a better time than respectable women in ancient Greece, at least by our modern standards, as they had more freedom and greater access to education. Phryne is written about in multiple sources so was clearly beautiful and bright enough to make a lasting impression. Now this is NOT a biography of Phryne (I wish), this is a discussion of sex workers in art, so let’s turn to a very famous (and, it must be said, very gorgeous) painting that depicts a sensational moment in ancient history.

Phryne was on TRIAL for IMPIETY, a capital offence (I mean she did allegedly model as a goddess so I’m not sure this helped her case). The story goes that the trial wasn’t going so well and the jury was about to vote, sentencing her to death, when her lawyer (who up until this point hadn’t exactly been on form) had a real lightbulb moment 💡

Right before the jury waddled off to cast their votes he had the bright idea of ripping her tunic open, baring her naked body to the room and asking them HOW could someone so beautiful, so physically perfect, commit the crime that she is accused of? As insane as this sounds, the Greeks really did believe there was a very strong connection between physical beauty and morality. She was promptly acquitted.

Look, when it comes to the veracity of this story, we really cannot claim that it definitely 100% happened but I refuse to have my bubble burst when it comes to the tale of a woman getting her ta-tas out and being acquitted of a literal crime. What does burst my bubble a smidge is the way this story ties into the objectification of women more broadly, particularly sex workers. The trial of Phryne inspired many other (male) artists, who were so taken with the titillating, mythologised moment, they felt compelled to immortalise her naked body on display to a room of men.

Here at least she’s at a festival so it feels a smidge less creepy/more celebratory and therefore closer to our fashion show starting point.

I’m very curious to hear your thoughts on this topic and the material I’ve whacked together for this newsletter ~ I’m very much still learning and reflecting and I’m honestly quite internally divided when it comes to representations of the female body in ancient art (and modern for that matter).

Let me know your thoughts ❣️

write ups of Sinéad O'Dwyer's SS ‘25 collection Everything Opens to Touch

www.cosmopolitan.com // hypebae.com // vogue.com

sources

Glazebrook, Allison, and Madeleine M Henry (eds). Greek Prostitutes in the Ancient Mediterranean, 800 BCE-200 CE. United States: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011.

Haynes, Natalie. The 'it girl' of the ancient world. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20171108-the-it-girl-of-ancient-greece

Keuls, Eva C. The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1985.

Lewis, Sian. The Athenian Woman: An Iconographic Handbook. Oxford: Routledge, 2002.

Neils, Jenifer. “Others Within the Other: An Intimate Look at Hetairai and Maenads. In Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, edited by Beth Cohen, 203-226. Leiden; Boston; Brill, 2000.

further reading

Kapparis, Konstantinos. Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2018.

Kurke, Leslie. “Inventing the Hetaira: Sex, Politics, and Discursive Conflict in Archaic Greece.” Classical Antiquity 16, no. 1 (1997): 106–50.

McGinn, Thomas A. J. Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Aspasia of Miletus was also charged and acquitted. Seems to have been a go-to rap.

Great story about Phryne. Thanks for starting my day on a high note.