sport as spectacle: the voyeurism of Olympic performance 👀

the objectification of modern athletes and the idealisation of physical perfection in classical antiquity ~ by Rosie Jakeways

****** a timely guest post by my dear pal and fellow classicist Rosie, which covers the ancient olympics, TikTok famous athletes, and the one and only BLUE DIONYSUS that took the internet by storm ******

Hey guys, gals, and nonbinary pals (thank you Thomas Sanders)! Rosie here – Cambridge MPhil graduate, mad sporting enthusiast (‘classicists can be jocks too’), and, like most of you I’m sure, keen follower of the Olympics over the last week or so. One of my interests during my masters has been the role of classics and classical material in establishing modern identities – the Olympics very much a case in point, so self-consciously modelled on an ancient concept, which is tied into both a sporting and an aesthetic ideal. This is very much a thought dump on the classical, the performative, the erotic and the viewer – or perhaps more of a mad thought spiral, attempting to negotiate all the different dynamics going on here, but I hope you enjoy it nonetheless.

Sport, at elite level, is spectacular. Take the Paris 2024 Olympics: from the opening ceremonies (with a smurf-esque costumed ‘Dionysus’ served on a platter to a crowd of drag queens) to the minutely televised sporting events themselves, the Olympics – and the elite sporting bodies it features, are intended to be viewed, and to be judged.

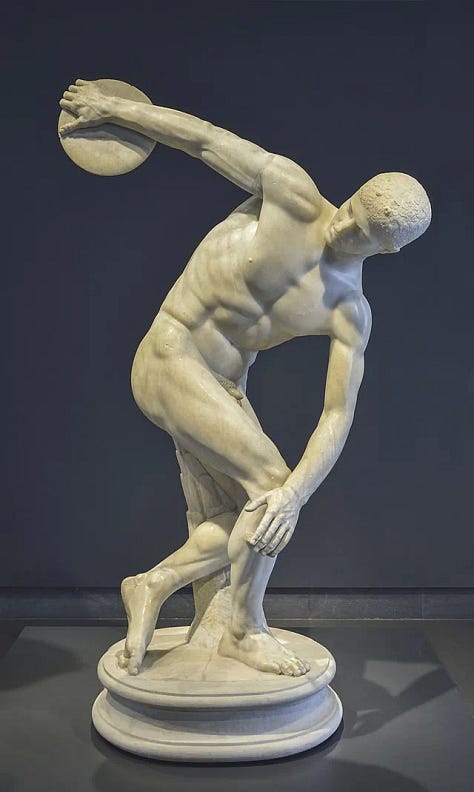

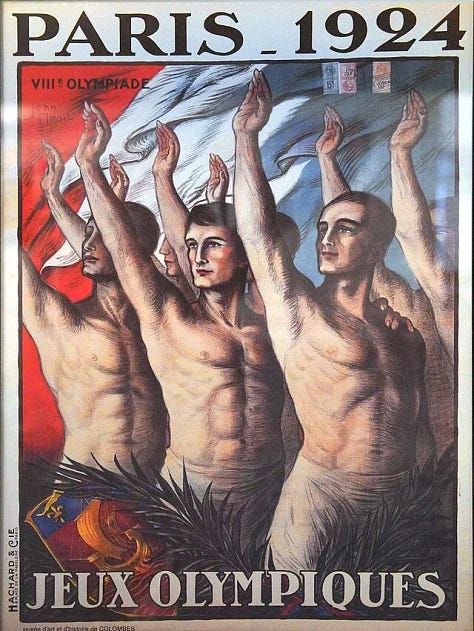

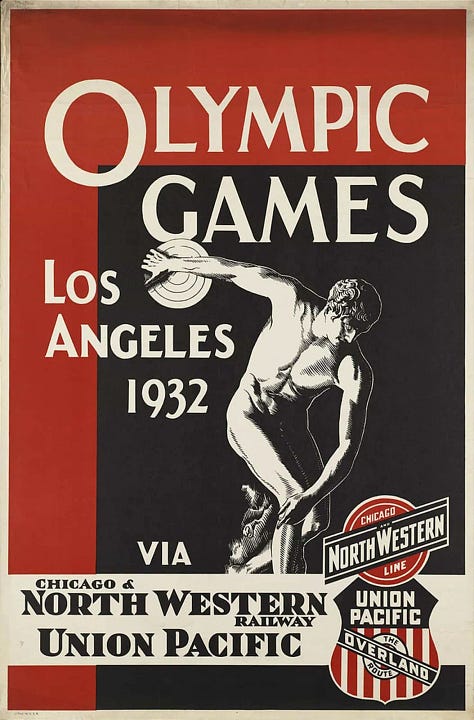

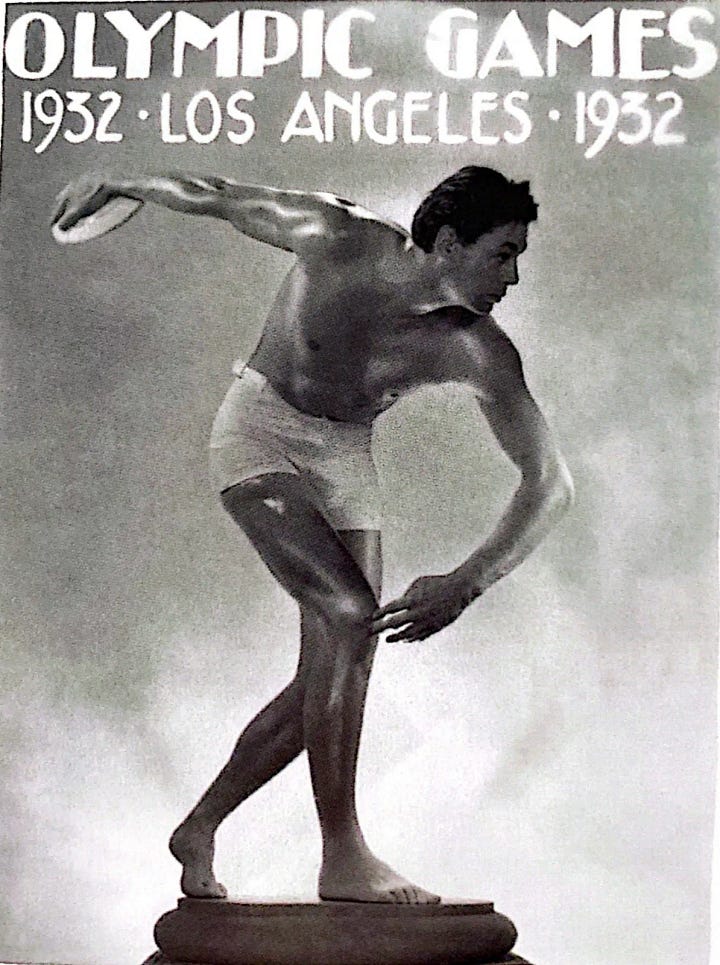

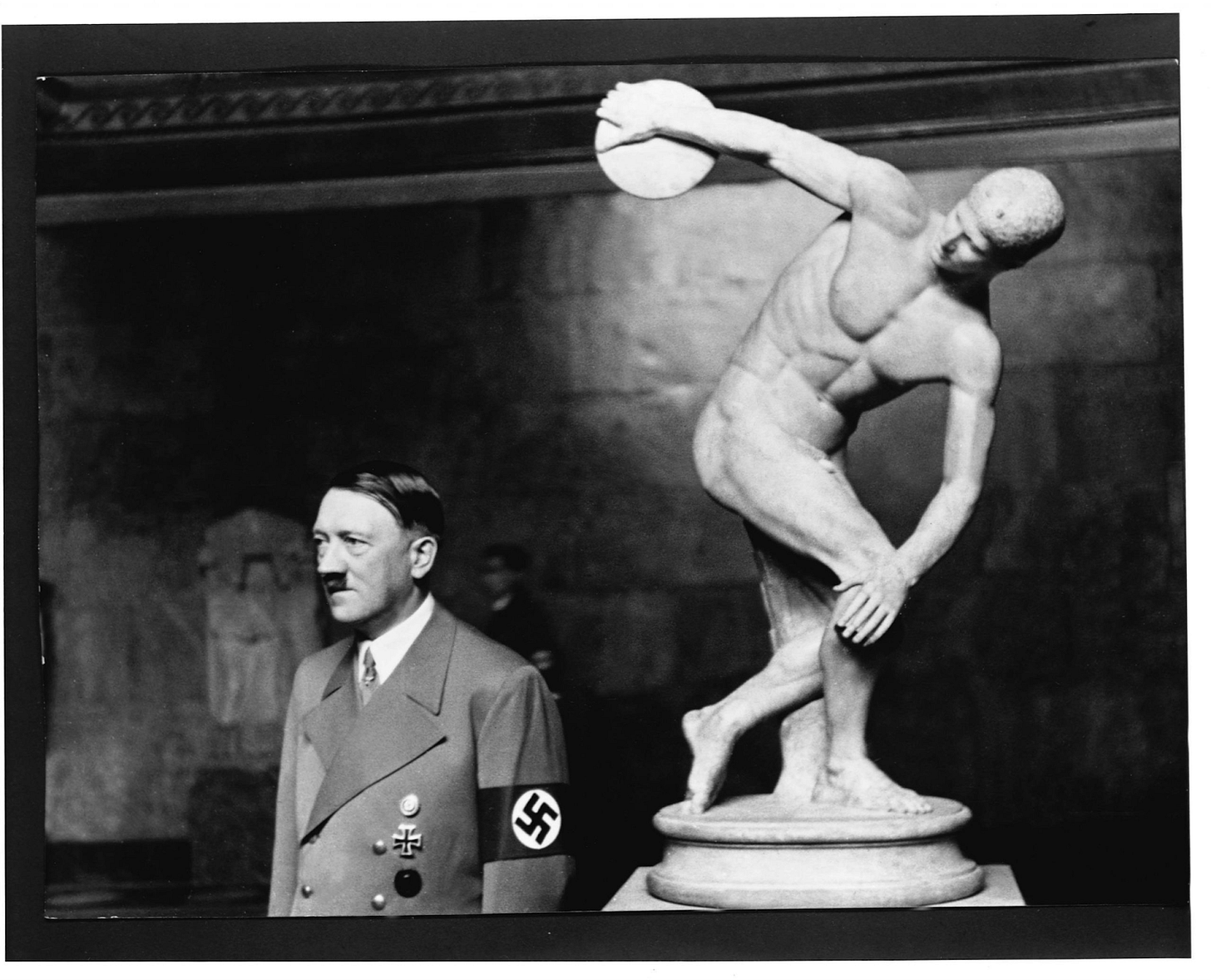

This spectacle is itself ancient, and modelled on an ancient ideal. As much is clear from posters advertising the games through to the 20th century: white, chiselled bodies reminiscent of the pervasive iconography of ancient sporting statues, or indeed posed as such; US swimmer Johnny Weissmuller poses as the Discobolos statue (‘discus thrower’, by the sculptor Myron in 460-450 BCE) in a poster advertising the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic games.

Modern sporting bodies are viewed in relation to the ancient games – or, specifically, to the modern idea of the ancient games as an ideal, both the pinnacle of sporting excellence and the pinnacle of beauty. This is the ideal which modern sportspeople are judged against – an illusory ideal, but one which hammers home the perhaps negative side to a tradition as long-lasting and as prestigious as this one.

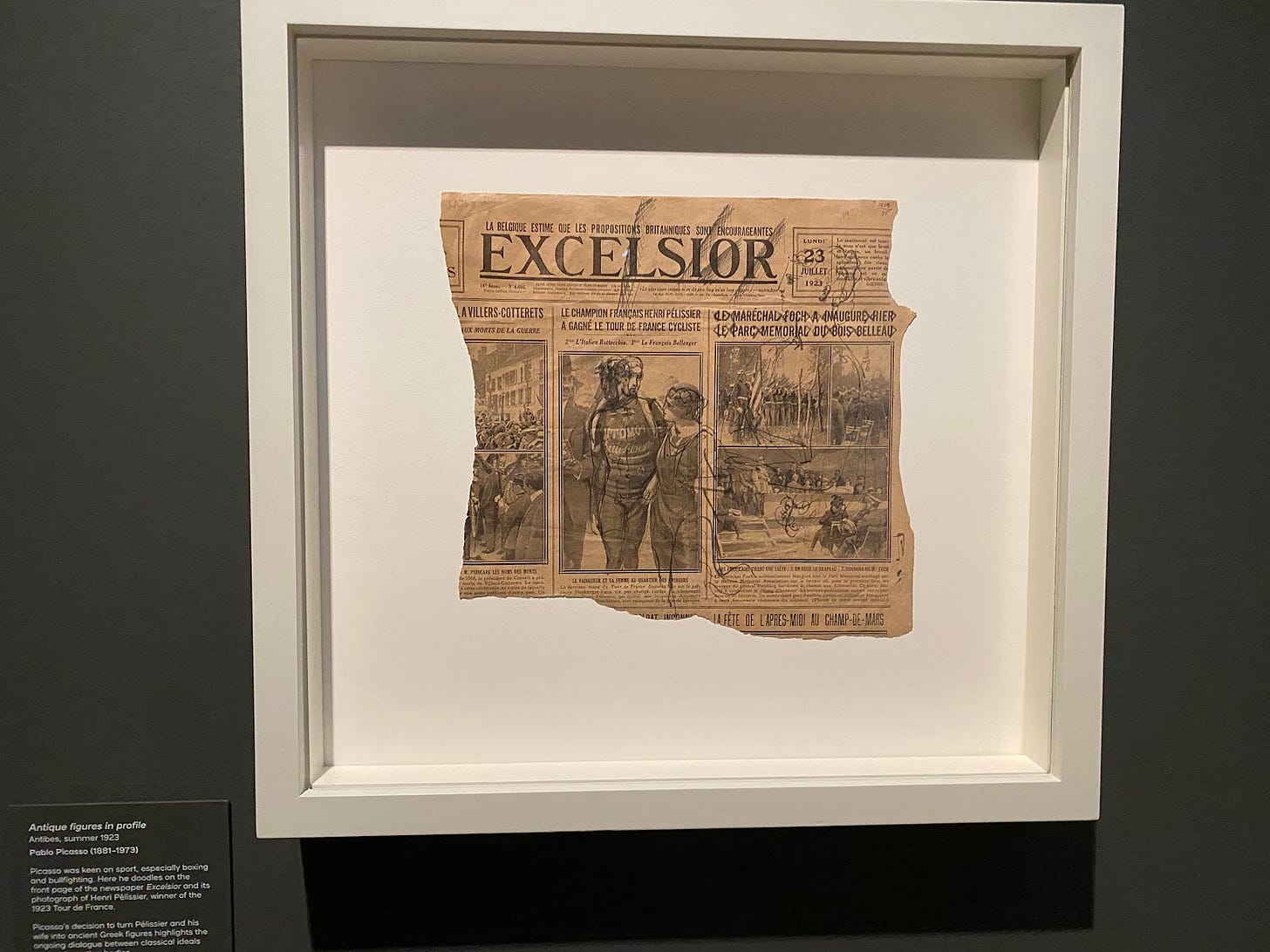

The widespread publication of images of elite sporting bodies allows comparison, and exposure of a supposed ‘deficit’, to this illusionistic ancient ideal; one which is fundamentally white, toned, and male. In an exhibition at the Fitzwilliam museum in Cambridge on the Paris Olympics of 1924, the first Olympics where technology permitted images of sporting bodies to be publicised en masse, Carrie Vout and Christopher Young aim to showcase the power of these bodies to challenge cultural assumptions; simultaneously, the images showcase our constant reliance on antiquity to dictate modern culture.

I focus here specifically on the function of audience; ‘voyeurism’ as a term to describe the relationship between viewer and athlete is potentially problematic, yet social media content produced around the 2024 Olympics has highlighted the sexualisation of athlete’s bodies, particularly women’s, and the pervasive idea that there is a ‘right’ way for an athlete to look. Elite sportspeople such as Ilona Maher, rugby player for team USA, and Célia Dupré, rower for team Switzerland, have both posted on Instagram to call out comments which criticise them for un-athleticism on account of their appearance. Voyeurism, then, speaks to the performative element of elite sport.

Perhaps the claim to ownership on the part of the modern viewer, or at least the ‘right’ to comment with semi-outrageous authority on the basis of a ‘correct’ athletic form, speaks to the pervasive iconographical power of classical statues such as the Discobolos. Statues are exhibitionist: typically created to celebrate victors in athletic contests they are intended to be viewed and admired, a testament as much to the skill of the artist as to the success of the athlete. Gymnos, the term from which we derive ‘gymnasium’, literally means ‘naked’; the nudity of the athlete allows somewhat for the creation of a wild fantasy.

The modern judge is perhaps overlooking the homoeroticism of such events. The ancient gymnasion was perhaps an exhibitionist but additionally a male-only space. In Plato’s Charmides, Socrates describes a general attraction on the part of the gym-goers to the young man whose name forms the title of the dialogue; a train of presumably all-male gym-goers follow him around, and Socrates himself is captivated by the beauty of his form. We do come across what is perhaps an attempt to control the sexuality of the athletes: the kynodesme, literally a ‘dog-tie’, used to tie the athlete’s dick and balls up and out of the way.

Potentially, this was for protection (in terms of comfort and practicality perhaps comparable to a sports bra); another potential reading is that this served to prevent an erection/ arousal, avoiding sex to conserve the athlete’s strength for the actual competition. Sexual moderation and restraint is also associated with small-dicked heroic male statues, in contrast to images of satyrs who, worshippers of Dionysus, are typically shown in scenes of excess – of alcohol, and of dick-swinging.

So the male sporting statues are, to an extent, charged with eroticism; albeit semi-off limits. Nude statues of women are more explicitly erotic: typically it is Aphrodite who is figured, who, as goddess of love and of sex, is intended to be viewed as attractive. The attraction the statues attempt to engender is part of her divinity, and of her danger. Take the statue of Aphrodite at Knidos; placed in an alcove, the temple setting encouraged the viewer to walk around the statue and admire her from all angles; one particular young man was so caught up in the statue’s beauty he ended up ejaculating on the marble, later throwing himself off a nearby cliff having been driven mad by guilt and fear at the insult to the goddess (Pliny, Natural History 36.20-21 for the placement of the statue and its sexuality; Pseudo-Lucian, Erotes 15).

Though stories of such explicit sexual entitlement on the part of the viewer are not linked to statues of male athletes, objectification in relation to physical form is present in both cases. Rather than life imitating art, living bodies are assimilated with (and held in comparison to) artistic ideals.

There is something incredibly voyeuristic in the natural comparison for modern sporting bodies being statues: almost an invitation for observation, admiration and desirability, which is incredibly discomforting particularly in a post-#MeToo age.

If we consider modern athletes effectively as reincarnations of ancient statues, then, inevitably our estimations fall short – but one singular perfect type of sporting body was a completely alien concept even in ancient Greece. An Athenian kylix (drinking cup) featuring four different athletes showcases not only four different body types, but bodies specifically adapted to the athlete’s sport – as indeed we see in the modern games.

The sprinter (far left) is highly skinny, especially in comparison to the boxer (second from left) who, holding the straps used to bind his hands, possesses a form very different to that of the Discobolos – yet is still, clearly, an elite athletic body. As ancient boxing competition was not regulated via weight class, being heavier was advantageous. The discus- and javelin-throwers (far right and second from the right respectively) are different once again, with more visible musculature. To consider only forms such as that of the Discobolos as the classical icon of sporting excellence is then, at least in part, illusory: specialist athletes’ body types varied across sport, rather than just appearing simply and stereotypically ‘athletic’.

It is certainly true, however, that athletes who competed in the ancient pentathlon (sprinting, javelin, discus, long jump, wrestling) were thought to be the most aesthetically beautiful, on account of their well-rounded muscular development. This is Aristotle’s take: in summary, (young) ancient pentathletes were the prettiest because they were both strong and fast (Rhetoric 1361b11). The takeaway from this is perhaps, at it’s most fundamental, that people who go to the gym and never skip leg day are the prettiest people around, but more crucially these are athletes who are deliberately developed to be well-rounded: the events of the ancient pentathlon were designed to mimic the kind of skills soldiers fighting in battle might find most handy. In comparison to specialist athletes, their skills were considered lesser. So the idea of one, specific, beautiful, ideal athlete who is simply the athletic form par excellence, one singular right way for a sporting victor to look based on a classical form, is an illusion – and for the critical viewer to force athletes into little boxes based on how they should look for peak performance is redundant at best and insulting at worst; investing a rather petrified form of classical iconography with far more power than is perhaps advisable in a modern world. These are the statues and images, after all, which fuelled the fires of 20th century fascism: the same Discobolos which Weissmuller poses as to advertise the 1932 Olympic games was purchased by Adolph Hitler in 1938, as emblematic of the perfect Aryan youth.

All of this to say that the stereotypical image of the muscular classical statue/athlete, which finds its way into so many dialogues of health and aspirational body type, and becomes a standard against which to measure athletes of the modern Olympics – is fake news, is illusionistic. There is no one ‘correct’ way for an athlete to look, but sporting events as spectacular can encourage consideration of modern, living people, in comparison to the ancient statues – nine times out of ten, and seemingly especially in relation to women, in a particularly unfavourable manner; encouraging objectification rather than appreciation of endeavour.

In many ways, the image of the blue Dionysus, served to a table of drag queens in the 2024 Olympics opening ceremony, is the perfect antithesis to the petrifying and fossilised classical iconography which still clings to the Games. Τhe image generated outrage - despite the International Olympic Committee’s description of the tableau, that ‘the interpretation of the Greek God Dionysus makes us aware of the absurdity of violence between human beings’, Christians worldwide saw the scene as a mockery of da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

Assimilation between Dionysus and Jesus is an equally fascinating rabbit hole, but its relevance here is perhaps more along the lines of people’s tendency to perceive interpretations of classical material along binaries of correctness. The classical is fluid, dynamic; the representation of Dionysus in drag is not only valid but established within the canon of ancient literature (see, for example, Aristophanes, Frogs 42-48: Dionysus attempts to dress as Hercules but appears to be wearing a woman’s dress, a source of great laughter on Hercules’ part). Reliance on a fixed set of images of sporting bodies - a particularly white, male, and masochistic form of athleticism, is perhaps disappointing - holding us to the impossible task of living up to the fabricated superhuman standards of the classical ‘past’.

Rosie Jakeways is a 22-year-old living in Cambridge, UK. She has an MPhil and a BA in Classical studies from the University of Cambridge. Her research has focused on classical reception and 21st century (digital) identities. She is passionate about sport, training rowing and triathlon, and adores travelling, writing, and photography.

Sources:

Spivey, Nigel. “The Greek Revolution.” In Greek Sculpture, pp. 16–53. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Vout, Caroline. Exposed: the Greek and Roman body. 2022.

Vout, Caroline, and Young, Christopher. Paris 1924: Sport, Art and the Body. 2024.

I read this and so many ideas popped into my head. Imagine a physical education class that was oriented around the Classics and those sporting activities or going to a gym that offered a classics based fitness regime that would become a thing like CrossFit.

ok, great article. did enjoy this a lot!