This week I’m going to walk you through a relatively innocuous ancient myth and poke holes in it until its more ominous, unsettling underbelly flops out.

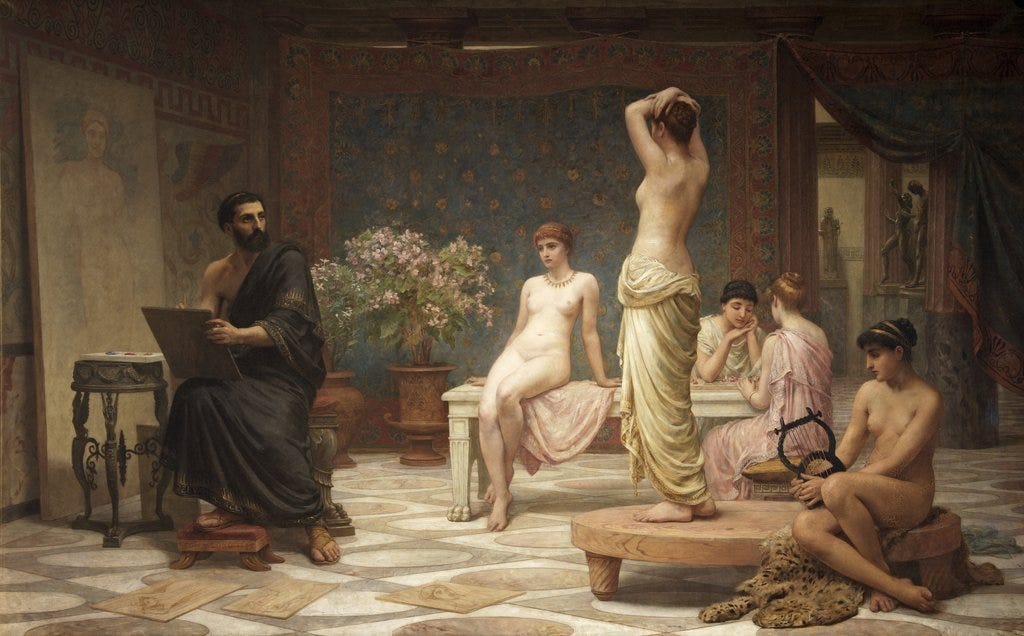

Now let’s get into the story of Zeuxis, a famous artist living in Greece in the 4th century BCE, who set himself the task of painting Helen of Troy.

Although a Greek painter and a Greek story, the Latin authors Cicero and Pliny give us the earliest known versions of the myth. Cicero, writing in 84 BCE, kicks his version off with the chronological equivalent of “once upon a time” but orients the story in the ancient town of Croton. Zeuxis, originally from Heraclea, apparently visited the town to decorate a temple dedicated to Hera. While he was there, Zeuxis put out a call for talent, asking for all the remotely attractive women floating around nearby to come through as potential models. Pliny, writing a century later, gives us a few more specifics; Zeuxis was born in 397 BCE and his career really got cooking in the early/middle fourth century BCE. Pliny also claims that Agrigentum was the site where the painter requested his parade of models, rather than Croton. This particular claim isn’t super convincing—Agrigentum was sacked by the Carthaginians in 406 BCE so it’s unlikely they had piles of money lying around to spend on art—but we work with what we’ve got.

What both Cicero and Pliny agree on, however, is how Zeuxis resolved his aesthetic dilemma, selecting the best parts of 5 models to create what was, according to his artistic vision, a faithful depiction of Helen.

We’ll get back to the Build a Bear of it all in a moment but just a quick aside, isn’t it a bit odd that Zeuxis wanted to paint Helen of Troy when he was decorating Hera’s temple? As the goddess of marriage, particularly marital fidelity, I wonder how Hera felt about Helen’s war-starting extra-marital dalliance with Paris? Helen as an artistic subject, too, is not exactly straightforward. The epithet used to describe her, “The face that launched a thousand ships,” is of course wonderfully romantic but also somewhat terrifying/ominous when you really think about it.

Back to the artistic pick n mix. Zeuxis’ choice of five models rather than one brings our attention to the shortcomings of nature, specifically the inability of a mortal, real woman to live up to the hype that surrounded (and still surrounds) the one and only Helen of Troy.

This brings us to mimesis, a fancy word that got thrown around a lot during my post grad that I’m still only on the verge of fully understanding, let alone using with any confidence. (A lot of the time at uni I felt like there was one particular seminar I missed which covered vocab as there were so many words I just smiled and nodded in response to, having not a single solitary clue what the hell they meant. Mimesis is one, along with ekphrasis and epigraphy. It felt far too embarrassing to ASK so I googled away in the privacy and safety of my own flat. We can get into the emotional and psychological hellscape of Oxbridge at a later date).

Here is the definition of classical mimesis, snatched from Elizabeth Mansfield’s book on Zeuxis:

“In its full, classical sense “mimesis” refers to a twofold approach to representation: first copying forms observed in nature, then generalizing or perfecting those forms to achieve a kind of ideal.”

Okay it’s relatively straightforward. Thanks to Ms Mansfield. I tore through her book while researching this topic and she took me down a wild, mimetic rabbit hole which I’m still in the process of crawling out of BUT I want to get into the Chimera, Frankenstein, and the fragmentation of the female so mimesis is only getting a smidge of airtime before we move on. That being said, let’s get Plato involved for a second.

What is the object of painting?

Does it aim to imitate what is, as it is?

Or imitate what appears, as it appears?

Is it imitation of appearance or truth?— Pl. Resp. 10.

In short, Plato wasn’t a fan of mimesis because it could distort and/or undermine truth. Mansfield makes a related point, that “classical mimesis wants to confirm the existence of the ideal but falters because it relies on the real as its model.” So a) mimesis can be dangerous as it messes with the truth and b) classical mimesis is somewhat cooked in and of itself, as it’s doomed to fail from the outset.

Mary Shelley gives us a more explicitly monstrous version of the Zeuxis myth in her novel Frankenstein. In this case a man creates a sentient, living creature from parts of cadavers rather than beautiful women.

If we hold up Zeuxis and Frankenstein next to each other, the boundaries between who created something beautiful and who created something monstrous in their pursuit of perfection starts to blur.

Shelley, along with the Neoclassical painter Angelica Kauffman, both flip the well-established gender dynamic epitomised by the Zeuxis myth, where the man makes art and the woman or women pose for it.

To really ram home the monstrous side of things, allow me to introduce the Chimera, a truly bizarre creature from Greek mythology. She (yes, she) had the body and head of a lion, a goat head sticking out from her back and a serpent for a tail. She also breathed fire. And had udders. My point is that Shelley isn’t the first to give us a more monstrous amalgam. The Greeks had their very own female Frankenstein (to whatever extent the Chimera can be classified as female), which provides a nightmarish counterpoint to Zeuxis’ Helen.

So, to recap, Zeuxis realised that none of the models he had access to could live up to an ancient ideal (yes, he’s ancient, but Helen of Troy and the Trojan War were ancient for him), so he created a composite, choosing the best attributes from five women to create his Helen. But this chimerical composite is an illusory fiction (I may or may not have based this entire newsletter around wanting to use the word chimerical as an adjective).

What’s more, the fragmentation of the female plays into the ultimate male fantasy.

Women, found lacking in the face of an impossible, unattainable ideal, are to be sliced, diced, and discarded.

Seems like a shitty deal, particularly as we don’t get to respond by breathing fire or bleating from our goat-head.

References

Cicero. De inventione rhetorica. 2.1-3.

Ione, Amy. [Review] Leonardo 41, no. 2 (2008): 187–88.

Mansfield, Elizabeth C. Too Beautiful to Picture: Zeuxis, Myth, and Mimesis. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2007.

McClure, Laura. Phryne of Thespiae: Courtesan, Muse, and Myth. Oxford University Press: 2024.

Plato. Respublica. 10.

Pliny. Naturalis Historia. 35.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. 1818.

For what it's worth, you're really growing on me as a writer! I love this more academic approach to Greek Mythology.

I love a good origin story. Was completely clueless about this Zeuxis dude. Thank you!