Achilles and Patroclus

A heart-rending poem inspired by love, loss, and the ravages of grief

At the risk of sounding absurdly cheesy and sincere, I feel truly honoured to be able to share this week’s guest post with you. Ever since I first heard this poem read live by my dear friend Ria Kealey, it has stayed with me. Ria kindly accepted my invitation to speak at one of my events back in Melbourne a few years ago and their work was so moving it had a few attendees in tears. I remember a handful of people coming up to me to discuss it, prefacing their praise with the admission that they weren’t familiar with the story but were nonetheless profoundly moved (and impressed). Looking at it again years later, it hasn’t lost any of that initial emotional heft (I may have gotten misty-eyed drafting this). Please enjoy.

(Ria and I decided to keep the introductory section the same with minimal edits so if the intro reads like a speech, that’s why).

The Story of Achilles in The Iliad (and his relationship with the darling Patroclus)

One of the great joys of the classics is how inherently human they are, how those universal themes come to the forefront regardless of the time in which something was written.

For a lot of queer people, the classics provide a remedy for the anxiety that comes from being treated like a trend or a modern invention. In the same way that the recognition of sameness from modern readers to ancient stories gives us an insight into the minds of ancient humans, that recognition of sameness can go further and validate identities that have been trivialised and dismissed. Queer stories and authors give us an anchor to hold on to, an ancestry that legitimises our existence, and when we can trace those stories back to the beginning of recorded literature, it feels like an undeniable declaration of our lives and loves. Regardless of whether the relationships and characters we see ourselves in are "canonically" queer, that doesn’t change the impact of their existence.

Beyond just the queer experience, seeing ourselves - our loves and losses, joys and griefs - reflected in literature is an incredibly comforting experience. I take great comfort in knowing that there is little originality left available to me - every sorrow and delight I feel has been felt a thousand times before, and somebody has probably written about it, whether in a love letter scrawled on the back of a receipt or an epic poem that has been spoken, transcribed and translated countless times, such as the Iliad. I feel honoured to continue on the vibrant and ancient tradition of poetry recitals tonight, but I want to begin by giving you all some context for the poem that I’ll be reading for you.

We begin with the story of Achilles.

Achilles was born of a sea nymph, Thetis, and a mortal king, Peleus, making him semi-divine. Before he was even born he was prophesied to become greater than his father ever was. As a boy, Achilles developed a close relationship with a young exiled prince, Patroclus. They were raised and trained together in Peleus’ household, and their bond was stronger than any other relationship Achilles had in his lifetime.

After years of training under the centaur Chiron, Achilles’ chance to claim his position as aristos achaion, the greatest of the Greeks, finally came in the form of the Trojan war. He takes his place as a general, Patroclus by his side, despite another prophecy that foretells either a long and happy life in obscurity, or eternal glory and an early death if he goes to Troy. In the tenth year of battle, Achilles withdraws from the fight over disrespect shown to him by Agemmemnon, leader of the Greeks. Without him on the battlefield, the Trojans quickly advance and for the first time in the decade of fighting, the tide is swayed. Despite offers of riches, Achilles refuses to rejoin the fight until the dishonour done to him is publicly repaired. He does, however, allow Patroclus to go in his stead, dressed in his armour and leading his troops.

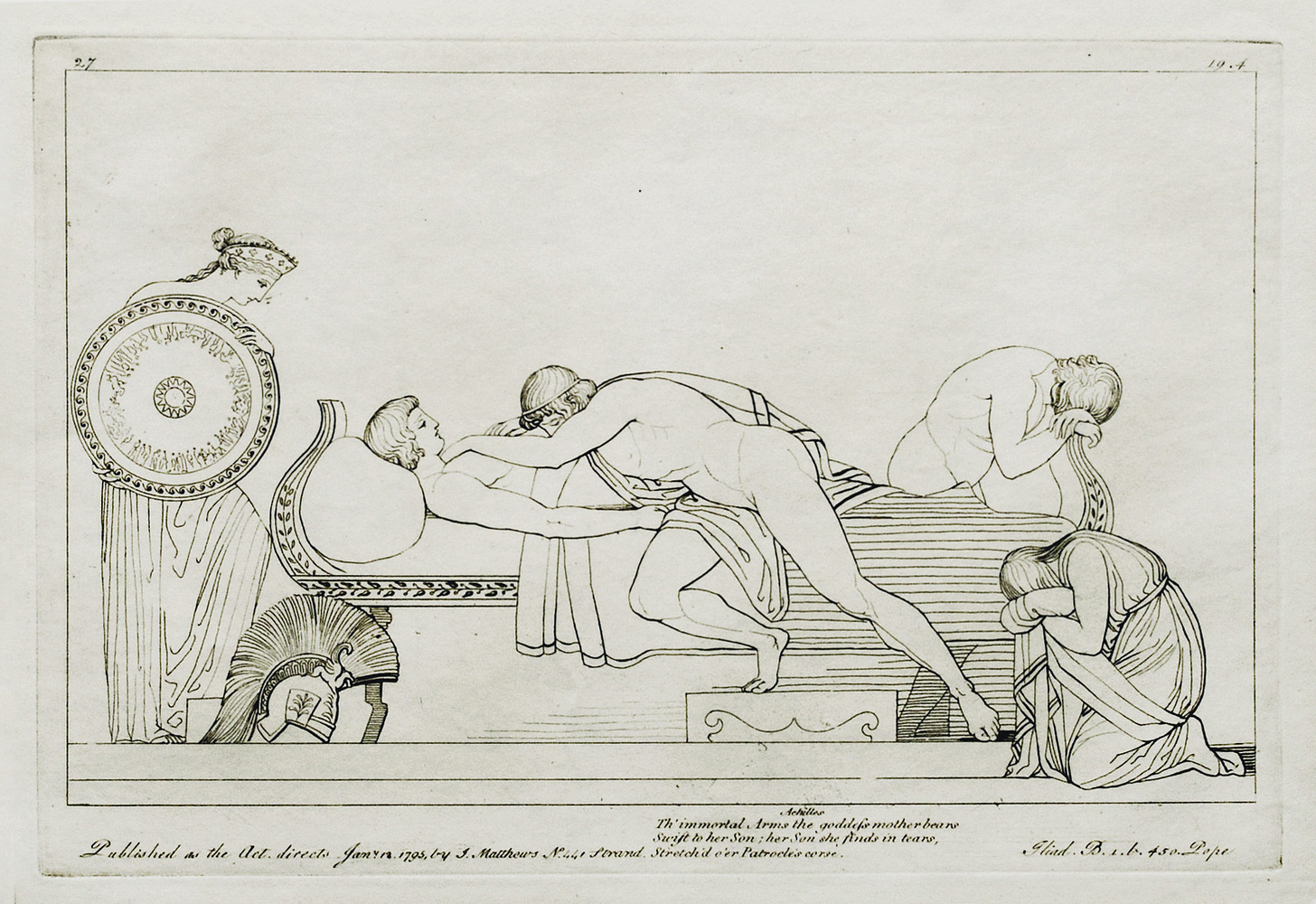

Hector, the greatest warrior of the Trojans, kills Patroclus on the battlefield having believed the ruse and mistaken him for Achilles. Achilles is devastated beyond belief when he receives the news. Homer describes him tearing at his hair, screaming, refusing to eat or sleep for days on end. He refuses to perform the funeral rites or bury the body until he has killed Hector. His mother comes to him and Achilles bemoans the fact that he has received everything he had wished for - eternal glory and riches, to be sung of as a hero for the ages - but at the loss of Patroclus, whom he calls "the man I loved beyond all others, loved as dearly as my own life". Thetis warns him that if he kills Hector, his own death is prophesied to follow shortly after, but Achilles doesn’t care, saying "I will pursue Hector who has slain him whom I loved so dearly, and will then abide my doom when it may please Zeus and the other gods to send it."

This is where we pick up. I wrote the following poem in the voice of Patroclus as his spirit lingers on earth after his death, unable to pass on until his funeral rites have been performed, begging Achilles to remember his humanity.

It is called Night Shift.

It was like this once: Every time my hands ached cold You would hold them in your own. Every bloody nose wiped pure by a lazy palm, Every knot in my hair persuaded out by your fingers. All those honeyed days in the water I saw you grow to divinity, The pike darting in shimmers from your spear, The blood from the one chosen trailing like widow’s tears. You always killed with grace, Said your blessings, Ate your fill and made use of the dead. Now I watch the eclipse draw ever closer, Your humanity thin as a waning moon. It is not for a mortal to question a god, But I am but an exhalation now, so I ask - Do you remember? The wild figs on the banks, How they burst velvet and sun-warmed on our tongues? The fossils on the riverbank, How they promised something bigger than us? Remember woodsmoke? Hyacinths? Hills expanding before us like a symphony? Remember how irreproachable we were? As if in the reflection of your shield I see us now: The body of a boy, fading into the arms of a god. In other words, love and grief In the same home, taking each other’s names. I see you tripping over yourself in your haste To come undone, darling, Hurtling swift-footed across the void to me On a bridge of bodies. You, heart-sick and choking on copper - Wash until the water stops rusting, Bury the dead where they do not whisper. I will still be waiting on the hill when the rivers run clear And blood no longer blooms from your knuckles like poppies. Til your blaze of glory runs to its end And all that remains is smoke and smoulder I linger here, shifting as a breeze amongst wildflowers, Waiting for the brush of your hand against mine, Light as the ash I’ll become.

Ria Sebastian Kealey (they/he) is a trans poet and editor living and working on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people. Their work can be found in Pure Nowhere and Soul Sighs, or experienced live at Saint Seb’s Salon, the monthly poetry event they run in Coburg. They hope you find yourself lovingly haunted by their words.

I wonder if any ancient bard celebrated the Theban Band, that deadly effective regiment of warrior-lovers that defeated the Spartans.

Consider me lovingly haunted by this beautiful work.